I didn’t want to be special. I didn’t want to be called on. I didn’t want to be taken into the room with no windows away from the others. But that’s what happens when your brain works differently in American elementary schools.

Anyone who has struggled academically knows the type of shame that is born in a classroom. This shame is a winged creature. It is a giant hunched next to your desk. It is also within you, mingling among your cellular organelles.

As a second grader, my shame around reading was invisible and yet I could feel it in every corner of my body. The people around me sensed it too. Sometimes adults tried to banish shame by giving it a name: special. But it was the 1990s, and all the other kids knew that special was a bad word even when adults pretended otherwise. Special did not defang shame. Instead, special fed the beast. So my shame grew silently between the pages of books that were assigned for class…I can’t remember any of those novels now. I don’t care to.

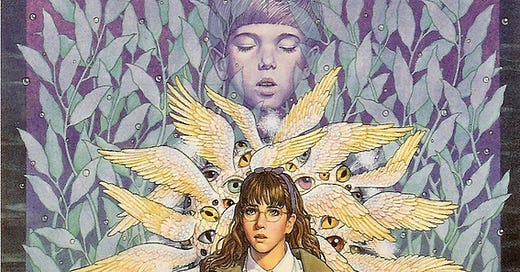

What I do remember is arriving home from school on a wave of relief and reading A Wind in the Door by Madeline L’Engle. This second book in the Time Quintet Series follows Meg Murray’s attempts to save her little brother, Charles Wallace, as the fabric of the universe frays inside his cells. I must have listened to the audio version of the first book in the series–A Wrinkle in Time–because I don’t remember ever handling a hard copy of the novel. But I remember curling up with my copy of A Wind in the Door (pictured above), holding the illustrations of Meg, Charles Wallace, and their interdimensional friends close to my heart. It probably took me three months to read all 240 pages, but I savored this book because it told a different story about school shame and the idea of special.

For those who haven’t read A Wind in the Door, one of the major premises of the novel is that Meg must protect her brother from the belittling teachers and administrators at his school–they believe he is special. They do not understand his genius. One memorable scene shows Charles Wallace’s first grade teacher asking each student to tell the class something about themselves. When Charles Wallace shares his interest in cellular biology (“What I’m interested in right now are the farandolae and the mitochondria”) the teacher chastises him for “making silly things up.” In this scene, and in many ways throughout the book, L’Engle scrutinizes the implication that there are natural hierarchies of intelligence. The characters each call upon their own special gifts, their own perspectives, and their varied abilities to save the universe. In L’Engle’s universe, each person is special. As Charles Wallace notes, from a cellular perspective, “a human being is a whole world.”

Reading A Wind in the Door made me feel big, even when school fractured my confidence. I read the book slowly. I didn’t recognize every word. I didn’t keep a vocabulary list. My parents read some of the story to me. But it was all joyful, shame-free reading because it was unassigned. And, for this reason, this book made me feel truly special.

This week on the podcast, Sarah Ropp and I talk about our first experiences with reading in school, reading joy, and children’s books. The next episode hits inboxes this afternoon. Subscribe to listen.