The tape deck was a juggernaut. At least eight pounds or more of beige plastic. I had to carry it around the house with two hands. Luckily it had a built-in, retractable handle for this exact purpose. It had a special compartment to stow its extra-long power cord. As a backup, it could power itself off of D batteries for a few hours, just in case the power went out. As an eight year old, the tape deck was my dream machine.

Technically, it didn’t belong to me. It belonged to the Library of Congress’ National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled. Once my application was approved, the NLS loaned me the thing to play specialty cassettes: books-on-tape I could pick out from their quarterly catalogue. The catalogues had everything from Beverley Cleary’s Ramona Quimby series to Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. The cassettes always arrived in the mail in an avocado-colored plastic container. Most books had at least two cassettes. I have this vague memory of each cassette being four-sided, but I’m not quite sure how that would be possible. I know for sure the tapes didn’t fit in my Fisher-Price tape player.

At first, I listened to books that were assigned in school. I’d plug my headphones in, open my paper copy of that month’s chapter-book, and read along with the narrator. This helped…sometimes. I started to recognize words on the page that had looked like hieroglyphics before. Words like inquisitive, cantankerous, and muffler. Sometimes my reading would outpace the narrator. Sometimes it would lag far behind. I tried to leverage the ingenious little knob that controlled the playback speed to match my reading pace, but this usually ended in disaster. Too slow, the book was suddenly being narrated by Eeyore. Too fast, the reader became Bugs Bunny.

In the end, listening to audiobooks made me aware of the fact that my eyes skipped around the page. It made me slow down and run my fingers underneath the words to keep my place and pace. It made me stop and note the words that were unfamiliar. It made my brain remember how much I liked stories, even if I didn’t yet like reading them.

Today, twenty-five years later, I’ve returned to this practice of reading with audio support as I try to teach myself Portuguese. The language is fairly new to me; I studied French in high school and moved on to Spanish in college. Luckily, Portuguese has a fair amount of overlap with Spanish giving me a leg up on some of the vocabulary. Still, I understand more than I can speak. And I can decipher sentences spoken aloud better than sentences that are written.

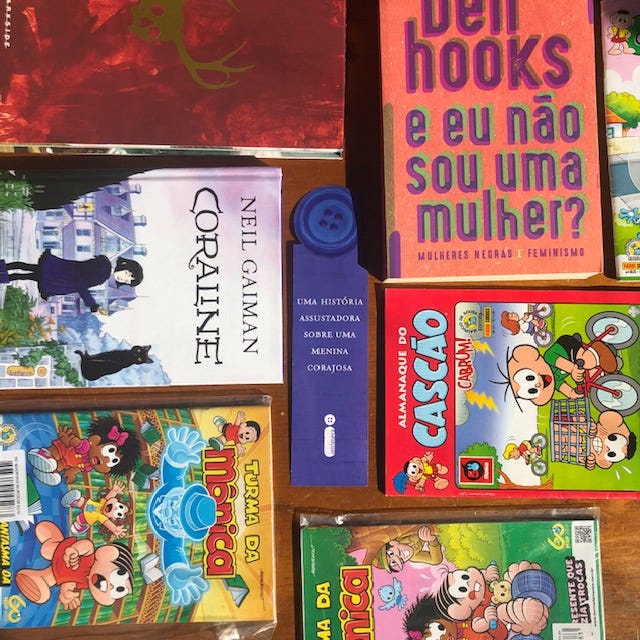

Knowing I would be spending some time in Brazilian bookstores this January (trailing my partner– a fellow bibliophile and a native Portuguese speaker), a friend recommended I try to read some old familiar novels translated from English to Portuguese. In addition to a handful of comic books (more on those later!), I chose a couple of translated works to re-read: Neil Gaiman’s classic middle grade thriller Coraline and bell hook’s first published book Ain’t I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism– translated to E Eu Nao Sou Uma Mulher which literally means ‘am I not a woman?’ (I know the question is meant to be rhetorical, but as a nonbinary person, I find this translation funny).

So, I tried to read these translated works. I’m not exaggerating when I tell you my iPhone overheated. I was furiously typing European-Portuguese words into Google Translate. I tried to take marginal notes of each unfamiliar word. This meant I was stopping and taking a lot of notes.

When I taught reading, we encouraged kids to use the ‘five finger test’ as a way to gauge whether books were too hard for them to access independently. Using their fingers, kids would count the words they didn’t know on a page. When they ran out of fingers on one hand, it was a good indicator that the book might be too hard to read on their own. In Portuguese, I was failing the ‘five finger test’ in a major way. It was slow reading. Too slow to be enjoyable. Suddenly, I was back in grade school with another loathsome reading assignment, the sentences barely linking into meaning. The story blurred beneath a sea of unfamiliar words.

After two weeks, thirty pages into Coraline, and two pages into bell hooks, I resorted to my old friend: the book-on-tape.

The well loved tape deck was gone, but I had access to both audiobooks via the New Orleans public library’s media app. I listened to both works at .78 speed with a highlighter in hand, noting the phrases/words that were unfamiliar to me in my Brazilian copy of each book. I had forgotten what the experience of simultaneous listening and reading was like. In reading a new language, I noticed myself reverting back to some of my same old reading habits from elementary school. My brain was speeding ahead of the narrator. Eyes skipping around the sentences, traveling back and forth. I bumped the narration speed up to .8 and made an effort to pause and digest the words. This helped. Sentences began to unlock themselves. Each one opened up like a precious jewelry box, each with its own array of gems.

By the end of Coraline, I could read a page without audio support and pass the ‘five finger test.’ I’m still reading bell hooks. While her work may seem like it would be harder to read than Coraline, the fact that it’s translated into Brazilian-Portuguese and uses academic language (chock full of cognates familiar to the English speaking reader) means that it’s been easier going. I’m enjoying soaking it in slowly.

Learning to read Portuguese has reanimated my memories of the dream machine, my government issued cassette player. The audiobook and the words on the page both demanded my attention back then. I had to notice what my eyes were doing, what my hands were doing, and what my mind was doing in order to fully experience the story. Somewhere in there, I was able to find synchronicity. In A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, George Saunders describes fiction as a ‘temporary mindmeld.” A reader spiritually travels into the mind of the character, and by association, the author. Using the dream machine was the first time I remember experiencing this mindmeld when reading independently. Reading in a language that’s new to me gives new life to this experience and makes me hungry for more of it. Thankfully, my new dream machine fits in my pocket.

____

I’ll be back in the coming weeks with more on reading (dis)ability and more recommendations for omnivorous readers. Don’t forget to subscribe to The Slow Read!